Examining extreme trauma bonds

With the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximating that 41% of women and 26% of men have experienced sexual violence, physical violence, psychological aggression or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime, (translating to over 61 million women and 53 million men in the United States) it’s clear that trauma-based attachments, significantly infiltrate mental health, relationship stability, and even physical health across generations.

Indeed, as a complex trauma survivor and therapist of over three decades, I can attest to the prevalence of relational abuse that runs the gamut from childhood neglect to malignant narcissistic abuse to domestic violence to sex trafficking, and everything in between. In all these scenarios, repetitious cruelty, devaluation, and intermittent positive reinforcement result in a trauma bond, a psychological connection in which cycles of abuse ignite a deep emotional attachment that the victim (mis)construes as love, loyalty, or dependency toward the abuser.

A common tactic in certain trauma-based relationships, especially in cases of childhood abuse, narcissistic abuse, exploitation, or coercive control, is grooming, a strategic, manipulative process where a perpetrator systematically gains control…

When grooming is prevalent, the abuser starts by building trust and emotional intimacy, leading the victim to feel safe or ‘special’ in the abuser’s presence. This makes it more challenging for the victim to recognize or admit the abusive behavior when it starts to gradually and slowly escalate.

Through the use of intermittent reinforcement, in which the abuser alternates between abusive behavior and moments of affection or kindness, the victim becomes emotionally hooked.

Chasing after fleeting moments of care or affection in the face of ongoing harm typifies the dynamic between the victim and the abuser.

Since the abuser consistently normalizes the abusive behavior and maneuvers to make the victim feel increasingly dependent on them, the victim begins to rationalize each new step of abuse, believing the relationship is still loving or worth fighting for. Over time, the victim becomes conditioned to accept the abuse, as it becomes part of a complex emotional cycle.

Once mired in psychological entrapment the victim starts to feel as if they can’t live without the abuser. Internalized feelings of guilt, shame, or helplessness, further deepens the bond.

Often, fears of abandonment or rejection keep the victim tethered.

What’s more, abusers often isolate their victims from support systems, making them feel completely dependent on the abuser for emotional, financial, or even physical survival. On top of this, victims often fear the consequences of defying or leaving the abuser, particularly if the threat of physical violence is a viable possibility. Given these conditions, the victim survives by rationalizing staying in an unsafe situation. The attachment may even be framed as providing a distorted sense of stability or familiarity.

In addition to trauma bonding, other related terms that describe the psychological dynamics of trauma-based relationships include traumatic attachment, Stockholm syndrome, betrayal bonding, pathological attachment, toxic loyalty, and dissociative bonding.

All these concepts pertain to unhealthy or maladaptive forms of attachment that develop in abusive or high-stress relationships. Shared key features include submission and an extreme emotional reliance on another person, even when the relationship is destructive. Furthermore, fears of separation or abandonment override logic or self-preservation.

That these sundry forms of relational trauma are ignited by attachment injuries with those in positions of power and dependency, complicates the victim’s ability to break free. Consequently, the victim is compelled to stay in the abusive relationship, group, or ideology irrespective of clear harm.

Critical to consider is how traumatic attachments are influenced by diverse variables such as psychological makeup, the severity and type of abuse, the length of the relationship, and external influences like social support or personal resilience. All these factors contribute to the tenacity of the trauma bond, making it difficult to break free even when the abuse is obvious.

A person’s psychological constitution, such as their temperament, coping mechanisms, and resilience, influences how deeply they form and maintain a trauma bond. For instance, folks with a history of attachment difficulties, low self-esteem, or those who have grown up in dysfunctional or abusive environments tend to be more vulnerable to forming trauma bonds. Their need for validation and emotional attachment is typically stronger, and they may have learned to tolerate or normalize unhealthy dynamics.

Correspondingly, such individuals may have incurred insecure attachment styles (like anxious or avoidant attachment), making them more likely to develop a strong emotional dependence on the abuser. Also, people raised in conditions of abuse and neglect tend to have a higher threshold for trauma or stress, meaning they can endure longer periods of abuse before their psychological defenses break down. This propensity can make a trauma bond stronger over time.

Scottish psychiatrist and psychoanalyst W. Ronald Fairbairn offers a profound lens through which we can understand these patterns seen in trauma bonding. Based on his observations of children who had experienced trauma, neglect, or difficult early relationships (1952), Fairbairn’s impressions led to ideas central to his theory of object relations and traumatic attachment.

Fairbairn posits that children are fundamentally relational beings who prioritize maintaining a bond with their caregivers even at great personal cost. He asserted that when caregivers are abusive or neglectful, children cannot psychologically reject them because their very survival depends on attachment. So instead, the child internalizes the bad caregiver as a split-off ‘internal object’ and blames themself for the abuse.

Because the child must make sense of the suffering while maintaining a connection to the caregiver, Fairbairn suggested that the greater the abuse, the stronger the attachment. The more extreme the mistreatment, the stronger the child’s unconscious hope that if they behave ‘better’ or ‘fix’ themselves, they will finally be loved.

Accordingly, the emotional bonds formed in childhood through trauma lead to complex, confused attachments where the person remains psychologically attached to the abuser, even while recognizing the harm they cause. Attachment and suffering become inextricably linked. These internalized conflicting representations (good and bad) form the basis for patterns of trauma bonding in adulthood, where the victim is emotionally torn between love and fear, dependence and pain. This intrapsychic conflict perpetuates the cycle of abuse.

What’s more, prolonged exposure to episodic cruelty, gaslighting, manipulation, and mind games makes the victim doubt their perceptions. Intermittent reinforcement intensifies the dependence. Amid confusion and an addictive emotional rollercoaster, the victim clings to moments of kindness as proof of hope.

Over time, the brain and body shifts into survival mode.

Stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline create a physiological dependence on the abuser. The body reacts to withdrawal similarly to substance addiction, and the victim becomes addicted to the pipe dream of ‘good moments’ returning. To continue ensuring safety the victim may unconsciously align with the abuser and come to associate both the pain and the occasional moments of affection or kindness with love or security. The victim may normalize, rationalize, or even justify the abusive behavior as something they deserve and something they can’t escape.

As the lines between love and abuse become continuously blurred, the victim is driven to seek affection or validation to survive emotionally. The spikes of kindness or reassurance after harsh episodes of abuse make the victim feel as though the abuser really loves them, even if the behavior contradicts this. To adapt to this situation and maintain illusions of safety, the victim will emotionally rationalize the abuse in order to mitigate the tension of cognitive dissonance.

Moreover, if a victim experiences an unconditional need for love, security, or survival, they are more likely to remain tied to the bond, as their dependency yearnings emanate from unmet emotional needs earlier in life, whether due to childhood neglect, emotional abandonment, or abuse. Subsequently, overwhelming needs for love or acceptance can cause the victim to cling more tenaciously to the abuser in an effort to satisfy unmet needs from childhood. Naturally, the abuser will capitalize on this predisposition by reinforcing the fantasy of a special unique connection that is irreplaceable or spiritually significant.

In due course, without the abuser’s approval, affection, or attention, the victim believes they would be worthless or incapable of functioning. At this point, when the victim’s self-worth is tied to the abuser’s treatment, the tormentor has become the redeemer. The abuser is perceived as a savior, necessary to one’s survival. The victim’s sense of self becomes entangled with the abuser’s perceptions, needs, and moods. Loss of the abuser feels like losing a core part of oneself. This sort of emotional dependency makes the bond incredibly difficult to break.

Educator and forensic psychologist Dr. Lenore Walker, who introduced the idea of trauma bonding in her groundbreaking work The Battered Woman Syndrome (1979), outlined a seven-stage cycle of abuse that delineates how victims become psychologically bonded to their abusers. Walker’s paradigm laid the foundation for understanding abusive relationship dynamics.

According to Walker, the cycle begins with the buildup of tension. Stress begins to accumulate in the relationship due to external pressures (e.g., work, finances) or internal conflicts. The abuser becomes increasingly irritable, critical, or controlling. The victim may feel like they are ‘walking on eggshells,’ trying to prevent an outburst.

This culminates in an abusive incident. The tension reaches a breaking point, leading to physical, emotional, verbal, or psychological abuse. The abuser exerts control through fear, threats, insults, or violence. The victim may try to resist or submit, but they are ultimately harmed.

After the abuse, the abuser may show remorse, apologize, or make promises to change. This is the reconciliation or honeymoon phase. The abuser may offer gifts, affection, or acts of kindness to regain trust. The victim, longing for love and stability, hopes the change is real. A period of calm encourages the victim to downplay the abuse. The relationship appears stable, and there may be a sense of normalcy. The abuser may be on their best behavior, reinforcing the victim’s hope that things have changed.

Over time, unresolved issues and stress build up again. Tension escalates, and the abuser becomes increasingly controlling, irritable, or aggressive. The victim senses the impending abuse and may attempt to pacify the abuser. However, the cycle repeats with another abusive episode, often worsening over time. The victim feels trapped, confuse,d and fearful, but may struggle to leave due to psychological conditioning, financial dependence, or hope for change.

Hence, the cycle continues, reinforcing the bond. Each time the victim forgives and stays, the trauma bond deepens. The intermittent reinforcement of love and abuse calcifies a powerful emotional dependency. The longer the cycle continues, the harder it becomes to break free. This repetitive pattern is why many victims stay in abusive relationships. The mix of fear, hope, and emotional connection makes escaping incredibly difficult, reinforcing the trauma bond over time.

Although letting go feels impossible, as the brain has been rewired to prioritize the abuser over self-preservation and fears of abandonment can feel worse than the abuse itself, breaking free can and does occur.

Believing one can survive outside the relationship requires immense inner work, often with professional support, to rewire the trauma-conditioned attachment and rebuild a sense of self. Dr. Walker’s work emphasizes that breaking free from a trauma bond starts with a fundamental understanding of the machinations of learned helplessness and the cycle of violence and its psychological impact.

Understanding that the emotional attachment isn’t love, that it’s a conditioned response to inconsistent treatment, is crucial to dismantling a traumatic bond. Ultimately one must dispense with false hope and fully accept that the abuser is unlikely to change despite apologies or promises. For this to occur, seeking trauma-informed support is crucial, as trauma bonds thrive in isolation. For survivors of domestic violence, Dr. Walker highlights the importance of shelters and advocacy programs.

Whether it be a trauma-informed therapist who can help unpack the bond and address underlying wounds, or finding others who have left similar situations and can support and validate your decision to leave, breaking the tenacity of a trauma bond requires empowering connections.

Also essential is strategic planning, especially when physical safety is at risk. This may involve having important documents and emergency funds ready, as well as identifying safe places to go and working with a therapist or advocate.

Breaking the psychological addiction necessitates going ‘no contact’, limiting exposure or making yourself as uninteresting and unresponsive as possible (aka grey rock method). Establishing distance assists with regulation, as trauma bonds often involve a chemical addiction to the highs and lows of the abusive relationship (dopamine from love-bombing, cortisol from stress). Likewise, it allows one to cultivate the necessary space to reframe beliefs about the abuser and oneself, process emotions, and rebuild self-worth.

Lastly, liberating oneself from trauma bonding is a courageous and comprehensive deep dive into unresolved childhood wounds (e.g., neglect, abandonment, or past abuse)and a journey of self-love and self-reclamation.

It is also a powerful trajectory towards dismantling challenging thoughts that excuse toxic behavior.

Tragically, those who are repeatedly victimized often excuse unrepentant perpetrators who were themselves victimized. This naive mindset enables abuse. Ones’ personal suffering is not justification for harming others. Irrespective of the universal plight of suffering and the multitudinous variables that comprise one’s unique nature, we are all responsible for how we manage adversity. While we cannot choose for another what choices they make, we can stop excusing depravity. Upholding standards that oppose victimization, while praising the strength of sincere contrition and the power to choose from a place of humanity, is a celebratory anthem for all victims who found the mettle to liberate themselves from bondage.

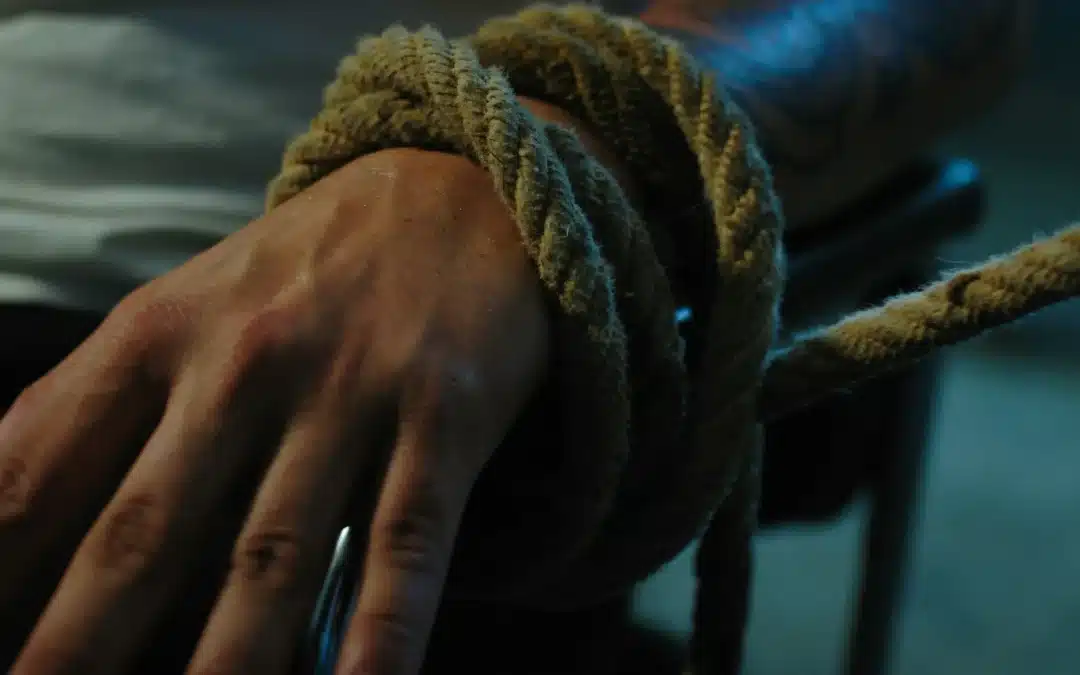

Photo by Jose P. Ortiz on Unsplash

Guest Post Disclaimer: Any and all information shared in this guest blog post is intended for educational and informational purposes only. Nothing in this blog post, nor any content on CPTSDfoundation.org, is a supplement for or supersedes the relationship and direction of your medical or mental health providers. Thoughts, ideas, or opinions expressed by the writer of this guest blog post do not necessarily reflect those of CPTSD Foundation. For more information, see our Privacy Policy and Full Disclaimer.

NYC psychotherapist & freelance writer. Survivor and thriver of Complex Trauma & Addiction. Dual citizen of the U.S. & Canada, traveler, lover of art and nature. I appreciate the absurd. Sheritherapist.com