Everyone experiences flashbacks. Most of the time flashbacks are benign when they experience a trigger, such as the smell of fresh-baked bread, and it reminds them of their grandmother.

However, flashbacks are a nightmare for those who have experienced extreme trauma in childhood or as an adult. This piece will concentrate on flashbacks that are part of the lives of those who live in the shadow of complex post-traumatic stress disorder.

What Are Flashbacks?

What Are Flashbacks?

Flashbacks, in PTSD, are where one relives a traumatic event while awake. Flashbacks are devastating to those who experience them, as they are suddenly and uncontrollably reliving something that happened in their past.

Flashbacks are akin to vomiting when having a stomach virus.

You cannot choose when or where it will happen.

Yet, flashbacks are not like a nightmare, where the person wakes to realize it was only a dream. People experiencing flashbacks become transported back to the traumatic event, reliving it with all its sights, sounds, and fears as if it were happening in the present.

The Differences Between Flashbacks from PTSD and CPTSD

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) is a complicated and new diagnosis that has yet to appear in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

One of the primary differences between PTSD and CPTSD is that post-traumatic stress disorder results from a single event, where complex post-traumatic stress disorder forms in relation to a series of traumatic events.

Normally, PTSD involves experiencing traumatic events such as the following:

- Car Accident

- Tornado or Other Natural Disaster

- Mugging

- Rape

These events, while highly traumatizing, are quickly resolved with emotional support from either friends/family, short-term psychotherapy, or both.

However, CPTSD usually involves traumatic and long-term abuse: physical, emotional, or sexual in scope. The following are a few examples.

- Sexual Abuse

- Emotional Abuse

- Neglect

- Physical Abuse

- Mental Abuse

- Domestic Abuse

- Human Trafficking

- Living as a Prisoner of War

- Living in a War Zone

- Surviving a Concentration or Internment Camp

Clearly, complex traumatic-stress disorder results from a different kind of traumatization than PTSD, and healing may take decades or even an entire lifetime.

The Amygdala, Hippocampus, and Flashbacks

To understand how flashbacks are such all-consuming and heart-wrenching experiences, we need to look at what is happening in the brain. The key players during flashbacks are the amygdala and the hippocampus.

The amygdala is responsible for processing emotional information, especially fear-related memories. The fear-response created by the amygdala evolved to ensure the survival of mankind by encoding the information of the threats we encounter as memories. This reaction prepares us for future encounters with the same or similar dangers.

The hippocampus is vital for the formation of long-term memory and catalogs the details of our experiences, so that recall of those events is possible. Normally, the hippocampus and amygdala work together to form new memories that become encoded in the brain for quick access later. However, traumatic events change this cooperative system into something quite different.

What Goes Wrong?

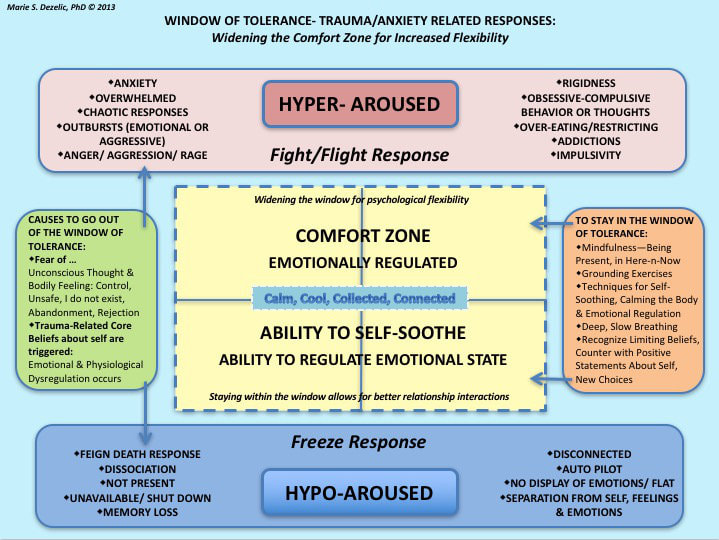

Another vital role of the amygdala is the recognition of danger, as well as sending out signals to our bodies to prepare for the flight/fight/freeze response.

Another vital role of the amygdala is the recognition of danger, as well as sending out signals to our bodies to prepare for the flight/fight/freeze response.

When the amygdala is over-stimulated by trauma, the hippocampus becomes suppressed, and the memory of that particular event can no longer become a cohesive memory. Instead, these memories become jumbled and force our amygdala to always be on the alert to any clues that we might be in danger.

After the threat has passed, strong, negative emotions leave our brains with a hodgepodge of images, sounds, smells, and senses of what just happened. Later, when encountering similar sensory input from our environment (triggers), we transport back to the original event and do not remember what caused the flashback to occur.

When encountering a sensory stimulus (trigger) that reminds us of the original trauma we experienced, our amygdala over-reacts and sets up a cascade of chemical events in our bodies to get us ready to fight, flee, or freeze. Thus, our brain sends us into a flashback, where we re-experience the traumatic event as though it were happening in the here and now.

There is no information stored by the hippocampus to tell our amygdala that the danger has passed.

Emotional Flashbacks

According to Pete Walker, emotional flashbacks are a complex mixture of intense and confusing reliving of past trauma from childhood. It is like living a nightmare while you are awake, with overwhelming sorrow, toxic shame, and a sense of inadequacy.

Filled with confusing and distressing emotions from the past, an emotional flashback is extremely painful.

In my experience, an emotional flashback causes me to feel nuclear war is about to begin, or I am in extreme danger. It just feels like something horrible is about to happen.

I become hypervigilant beyond my normal and want to isolate away from family and friends. Unfortunately, doing so only magnifies the feelings of abandonment, and I get stuck in a loop of feeling in endangered and trying to reason my way out of my feelings of hopeless despair.

To make matters worse, I hear my inner critic repeating messages given to me in childhood, calling me a loser, a nobody, a failure, and not a good person. These old tapes leave me without energy and sometimes feeling self-destructive.

Emotional Flashbacks and the Brain

Chronic exposure to abuse in childhood often leads to the development of complex post-traumatic stress disorder, leaving the victims, now adults, reliving the abuse over again later in life in the form of emotional flashbacks.

The original traumatic events harmed the brain’s ability to calm down from a potential or perceived danger recognized by an overactive amygdala.

To better understand this reaction, one must first comprehend two parts of the automatic nervous system (ANS), the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. More on this interaction below.

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS)

A wonderful description of these vital brain regions in an article written by Doctor Arielle Schwartz from 2016 titled The Neurobiology of Trauma, it states: “The autonomic nervous system (ANS) plays a significant role in our emotional and physiological responses to stress and trauma. The ANS to have two primary systems: the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system.

The sympathetic nervous system is associated with the fight or flight response and the release of cortisol throughout the bloodstream.

The parasympathetic nervous system puts the brakes on the sympathetic nervous system, so the body stops releasing stress chemicals and shifts toward relaxation, digestion, and regeneration.

The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems are meant to work in a rhythmic alternation that supports healthy digestion, sleep, and immune system functioning.”

Dr. Schwartz goes on to describe how the “rhythmic balance” between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems becomes disrupted by chronic child abuse, and that this lack of synching of the two leads to problems later.

During an emotional flashback, because your ANS is damaged and uncoordinated, the amygdala recognizes what it perceives as danger (trigger) and reacts, triggering the fight/flight/freeze response. This reaction engages the sympathetic nervous system revving up your body and causing a significant amount of distress.

However, unlike under normal circumstances, the parasympathetic nervous system does not engage in calming down the situation leaving a person stranded in yesterday.

Managing Flashbacks

No chapter about managing emotional flashbacks would complete without mentioning Pete Walker, a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist, and the author of several books, including The Complex PTSD Workbook and Complex PTSD, from Surviving to Thriving. He is also a person who has lived experience with CPTSD and emotional flashbacks.

Included in the work, Complex PTSD from Surviving to Thriving are thirteen steps to manage flashbacks. You can find Pete Walker’s thirteen steps to managing emotional flashbacks in the next several paragraphs.

The Thirteen Steps to Managing Emotional Flashbacks

Say to yourself: “I am having a flashback.”

Flashbacks take us into a timeless part of the psyche that feels as helpless, hopeless, and surrounded by danger as we were in childhood. The feelings and sensations you are experiencing are memories that cannot hurt you now.

Remind yourself: “I feel afraid, but I am not in danger!

I am safe now, here in the present.” Remember, you are now in the safety of the present, far from the danger of the past.

Own your right/need to have boundaries.

Remind yourself that you do not have to allow anyone to mistreat you; you are free to leave dangerous situations and protest unfair behavior.

Speak reassuringly to the Inner Child.

The child needs to know that you love her unconditionally- that she can come to you for comfort and protection when she feels lost and scared.

Deconstruct eternity thinking in childhood, fear and abandonment felt endless – a safer future was unimaginable.

Remember, the flashback will pass as it has many times before.

Remind yourself that you are in an adult body with allies, skills, and resources to protect you that you never had as a child.

Feeling small and little is a sure sign of a flashback.

Ease back into your body. Fear launches us into ‘heady’ worrying or numbing and spacing out.

Gently ask your body to Relax: feel each of your major muscle groups and softly encourage them to relax. Breathe deeply, find a safe place to soothe yourself, and allow yourself to feel the fear without reacting to it.

Resist the Inner Critic’s (more about the Inner Critic in another post) Catastrophizing.

Use thought to stop the inner critic’s endless exaggeration of danger and constant planning to control the uncontrollable. Refuse to shame, hate, or abandon yourself. Channel the anger of self-attack into saying NO to unfair self-criticism.

Use thought substitution to replace negative thinking with a memorized list of your qualities and accomplishments.

Allow yourself to grieve.

Flashbacks are opportunities to release old, unexpressed feelings of fear, hurt, and abandonment, and to validate – and then soothe – the child’s experience of helplessness and hopelessness.

Healthy grieving can turn our tears into self-compassion and our anger into self-protection.

Cultivate safe relationships and seek support.

Take time alone when you need it, but don’t let shame isolate you. Feeling shame doesn’t mean you are shameful. Educate your intimates about flashbacks and ask them to help you talk and feel your way through them.

Learn to identify the types of triggers that lead to flashbacks.

Avoid unsafe people, places, activities, and triggering mental processes.

Practice preventive maintenance with these steps when triggering situations are unavoidable.

Figure out what you are flashing back to.

Flashbacks are opportunities to discover, validate, and heal our wounds from past abuse and abandonment. They also point to our still unmet developmental needs and can provide motivation to get them met.

Be patient with a slow recovery process

It takes time in the present to become un-adrenalized, and considerable time in the future to gradually decrease the intensity, duration, and frequency of flashbacks. Real recovery is a gradually progressive process (often two steps forward, one step back), not an attained salvation fantasy.

Don’t beat yourself up for having a flashback.

Flashbacks happen without your consent and certainly without you wanting them to occur. So, why beat yourself up over something you have little control.

Grounding Techniques to Defeat a Flashback

The reason flashbacks are so powerful is that they unground one from the present and propel them back to the past. Grounding techniques can help a person reground themselves in the now and are a powerful tool in healing from any trauma.

The reason flashbacks are so powerful is that they unground one from the present and propel them back to the past. Grounding techniques can help a person reground themselves in the now and are a powerful tool in healing from any trauma.

Some grounding techniques are listed below:

If possible, say out loud to yourself the following questions (If you cannot speak out loud, then say them in your mind):

- Where am I?

- What is today?

- What is the date?

- What is the month?

- What is the year?

- How old am I?

- What season is it?

Physical sensations are important to ground ourselves. Try doing some of the following:

- Hold a pillow or stuffed animal.

- Hold a piece of ice in your hand.

- Listen to music.

- Name 2 things you can see in the room with you.

- Name 2 things you can hear right now.

- Pay attention to the movement of your abdomen as you breathe.

Sometimes a Visual reminder is needed to help stay grounded. Keep these items with you or within sight:

- Pictures of important people in your life today.

- A calendar with the current month and year.

- A locket with a picture of someone important today.

Practice deep breathing:

- Take deep breathes in through the nose and blow them gently out through the mouth.

- Breathe from the diaphragm (gut), not from the chest.

- Repeat as many times as necessary to calm down and re-center.

Healing is Likely

It is vital to remember that what is happening, the overstimulated ANS, the flashbacks, and the need for grounding techniques will not be a forever struggle.

One can heal from severe trauma.

Healing begins when one understands that they are and never were responsible for what happened to them and that it is now up to them to get better. There are no other ways to achieve healing. One cannot go under, over, or around it, the only way out is through.

Understanding why one can feel so bad and suffer from flashbacks is part of taking power away from the past and those who hurt you. Keep going, never, ever give up.

Never.

“It always seems impossible until it’s done.” ~ Nelson Mandela

“Most of the important things in the world have been accomplished by people who had kept on trying when there seemed to be no hope at all.” ~ Dale Carnegie

“Tell them it will take them longer to heal than what they want, but not as long as they fear.” ~ Paula McNitt PhD

Resources:

Schwartz, A. (2016). The Neurobiology of Trauma. Retrieved from:

https://drarielleschwartz.com/the-neurobiology-of-trauma-dr-arielle-schwartz/#.XpSvIchKjIV

My name is Shirley Davis and I am a freelance writer with over 40-years- experience writing short stories and poetry. Living as I do among the corn and bean fields of Illinois (USA), working from home using the Internet has become the best way to communicate with the world. My interests are wide and varied. I love any kind of science and read several research papers per week to satisfy my curiosity. I have earned an Associate Degree in Psychology and enjoy writing books on the subjects that most interest me.

Hello

As a sufferer of C-PTSD. There seems to be a trend to downplay or simplify the issue,, This is not like stubbing one toe in the middle of the night or paper cut,, Some ice will solve this or listening to your favorite song, This can and does for me have serious compilations that last for days if not weeks and really adds to the stress of matters,

I’m sincerely sorry if you felt I was downplaying flashbacks. Believe me, that was not my intention. I too have flashbacks every day and they can be a big problem for my ability to function. I also have CPTSD and another severe mental illness and understand all too well what suffering comes from flashbacks. Shirley

I think these are wonderful techniques but I am struggling with even recognizing that I am having an emotional flashback because what I feel at the time is so very real I have no idea that I am flashing back until I finally lose it and then I have to look back and see what caused me to become unstable. I have discovered it has to be this. I don’t know what is triggering me or how to tell if I am really in danger because once I am hyper alert, I feel that I am overreacting and don’t actually know I am hyper alert but my subconscious mind is confirming to me through people that I can’t trust them, they really are against me and I am not safe and there seems to be no reasoning in my mind. It really seems true and very real. Afterwards I feel shamed and like a failure for behaving so out of character and acting so insecure and childlike and accusing people I love of hating me and wanting to harm me. That is difficult for them to have to endure. All of this out of nowhere? How can I know that I am flashing back? I feel trapped and scared because I don’t know when it could happen again. I am trying to explain this to my husband but it’s difficult for him to comfort me when I am accusing him of wanting to hurt me. He is taking it personal which I can understand if your wife out of nowhere accuses you of hating her and the children and not being safe with you and appears to seriously believe it and after I melt down have no idea why I did that thought that or any explanation at all? He can’t understand because I don’t even understand what is happening. He thinks I must secretly hate him or think he is a failure but I really don’t. I don’t know what to do about this. It is new to us. It started 2 years ago so he is not used to me this way and I am not either.

Have you sought the help of a mental health professional who is trained in trauma-informed care? They may be able to help you learn the signs that you are triggered and about to meltdown. Pay attention to your body because it is the first place that will react. Know your triggers and learn to respond with grounding techniques. Again, a therapist can help you. It may be that your husband will require therapy too so he can understand better what is happening to you and that it is not his fault. I feel for you. I’ve been where you are. It’s a frightening and disturbing place to be. I hope you will consider getting some help. Shirley

Got days where it’s one long infinite loop of flashbacks n navigating triggers while managing the anxiety attacks while working hard to breathe n apply all the advice.. n not retreat or avoid..by days end overwhelmed with depression…but I refuse to give up n be definded by cptsd..just gotta keep unraveling the triggers

Thank you for the thorough article. I especially appreciate the 13 steps. I’ll refer to this many times over.

I’m so glad the article helped. Thank you for your comment. Shirley

Thank you for the informative article. I didn’t realize that what I was experiencing was an ’emotional flashback’ giving it a name helps. Mine too last for hours to a few days at times. I appreciate the scientific explanations as it helps to understand what the body is going through. I am glad I found this site.

We are glad you found our site and that you found this article so helpful. Shirley Davis

Thank you for this very helpful article. Working through it helped me deal with a flashback just now, and I gained some insight into how my past is affecting me.

One thing I’d like to see made clearer, is the difference between PTSD flashbacks, and flashbacks that are experienced from CPTSD. The article describes PTSD flashbacks as reliving traumatic past events. However, CPTSD flashbacks aren’t reliving the events themselves; they’re reliving the _emotions_ associated with the events. Fear, anxiety, shame, helplessness, hopelessness– those are the emotions we “flashback” to and feel as we did during the trauma we experienced in the past. (Often I can’t even identify or remember the events behind the emotional flashback. That’s part of working through the emotional flashback: to discover what events caused those feelings, so I can try to resolve the past and therefore resolve the feelings I’m suffering through in the present.)

The article hints at this difference between the two types of flashbacks, but perhaps it doesn’t make it as explicit as someone may need it to be in order to identify their own emotional flashbacks.

Thanks again, I always find your articles helpful!

Thank you for your input and feedback. I will most certainly take your suggestions about flashbacks into consideration for future articles on this subject.

Having flashbacks just arrives out of nowhere. In my case, they are caused by four and a half years of infidelity by my husband with his mistress. The affair crushed me totally because my marriage was based on total trust on my part. There were so many lies and deceptions over time even after the affair was discovered and ended that I have no control over when flashbacks and panic attacks occur. Deep breathing and other techniques have limited effects because my trust has been compromised by the person who I loved unconditionally for almost 30 years, betrayed me for several years . During that time, he did whatever he wanted with the idea of never getting caught and the mistress was on board with every filthy thing aimed at destroying me and my marriage. My husband thinks it happened in the past so I have no reason to relive something that is over. He doesn’t understand the measure of hurt that was done to me and to us as a couple. Love is still there but trust is a challenge. I need help to rid myself of the demons that come as flashbacks and panic attacks.

Lyn I am having a lot of problems with panic attacks from this as well. In my case it was emotional abuse from my mom and brother. I am sorry for you. Keep healing, it will get better.

Thank you for your honesty

This clinic is very clean and organized. All staff

is educated and knowledgeable. I never have to wait more than a couple of minutes.

The recovery support specialist is more than happy to help with finding resources.

I appreciate that she truly understands what patients are going through!

Good article but one thing I’d like to comment on is the following:

“These events, while highly traumatizing, are quickly resolved with emotional support from either friends/family, short-term psychotherapy, or both.”

The words “quickly” and “short-term” here seem inappropriate. Everyone’s experience is different and no one’s recovery from trauma follows the same timeline. Yes, in the context of ptsd vs cptsd, recovering from ptsd will most likely be a lot quicker than from cptsd but to say it’s “quickly resolved” feels rather simplistic and invalidating to those struggling with ptsd.

Thank you for the correction. I didn’t mean to invalidate anyone’s experience. I’m glad you called me on it. Shirley

I suffer from flashbacks all day every day with maybe a total of 20 minutes a day tops when I’m not having a flashback. Then when I go to sleep I dream about the past all night long and remember everything in the morning. I also have premonitions and always l ow before something bad happens now.

Thank you so much for this article. It has already helped me so much to understand what is going on with me. I am 63 and my mother and brother were narcissists. I was the scape goat and I have these emotional flashbacks frequently. I have been healing for about 25 years now. I went no contact with both when I was 40 and it was very difficult to do, but definitely the right thing to do. Again, thank you so much.